You might have heard your dyslexic child say the following:

“What is wrong with me, Mum?”

Hmm, yeah. What is actually wrong? Is there anything wrong?

There is only something “wrong” with your dyslexic child because our schools and societies are built around the ability to read and spell.

If it were not like that, no one would find out that your child finds it difficult to make the letters make sense.

But even as a dyslexic person, I have to say that it is quite nice to be able to read and write. It creates a lot of opportunities to communicate and share knowledge.

So yes, in a way something might be wrong with us dyslexic people when the outside world creates demands on our reading and spelling abilities.

BUT I’d rather say that we are different.

That is because the only thing that is “wrong” with us is that our brains work in a slightly different way than those of people who do not have dyslexia.

Here, I will explain how our brains are different, how we can still read, and how we remember. And how you remember.

In this article, you will learn more about:

- how the brain works when we read

- how the dyslexic brain compensates when it has to read

- how the working memory functions

My child is dyslexic

“What is dyslexia, and what does it mean for my child?” Have you also been searching for answers to that?

Understand your dyslexic child

It can be challenging to be a parent and help with the homework without getting frustrated.

Use the apps and tools

Have you also thought about what apps and programs that are best? Then your child could get their homework done without issues…

THE BRAIN IS AN ASSEMBLY LINE

It is quite simple.

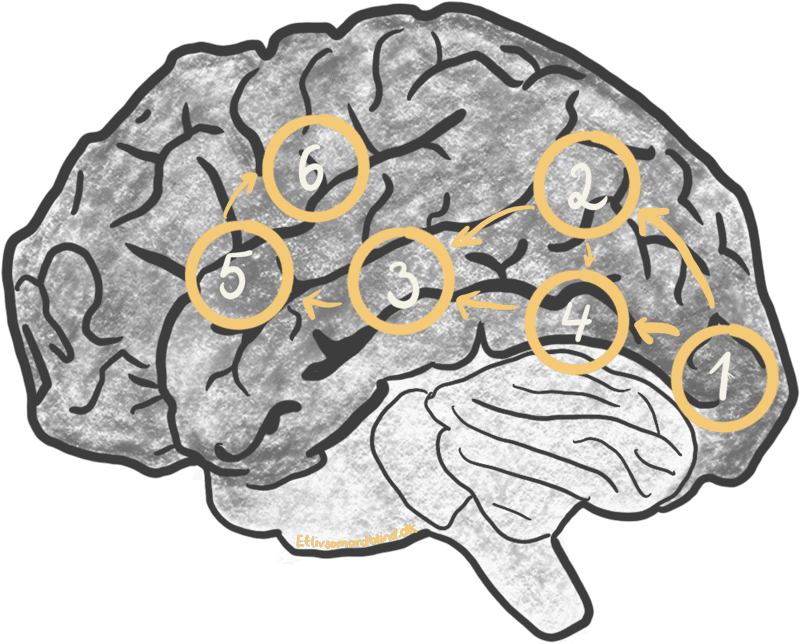

All brains can be divided into several areas, and each has a task on an assembly line where letters turn into words.

There is an area in the back of the brain that detects our visual sensations (1). Another area catches and connects what we hear with what we have seen (2).

The areas work together and ensure that we, for instance, know that the cow moos and the dog barks.

When it comes to reading, that concerns a third area of the brain, which ensures that we can distinguish different language sounds from one another (3). A fourth area ensures that we can remember both the sound and the spelling of words and parts of words (4).

A fifth area generates language about what we read, so we are ready to read out loud (5).

The last area in the brain kickstarts the muscles around the mouth, tongue, and neck so we can speak what we read (6).

This assembly line of activity happens in the brain’s left part and is often called “the language area” in everyday speech.

The activity on the assembly line happens so quickly, and partially simultaneously, that we do not register it happening.

Researchers disagree on where the challenge for dyslexic people occurs. Still, the common denominator for the studies of dyslexic brains is that there is less activity between two or more of the areas on the brain’s assembly line.

Remember that this is only a simple explanation of what is happening in the dyslexic brain. But the brain is a huge factory, where many things happen simultaneously. Many processes are going on at the same time, so if your child has issues with breaking the enigma of letters and words, there might be other causes that interfere with the assembly line for reading.

Fortunately, the brain is plastic. That means that it works like a muscle. If one area is less active and cannot become more active, then the brain’s other areas can be trained to compensate for the less active areas.

SO HOW DOES THE DYSLEXIC BRAIN READ?

First of all, there are different degrees of how dyslexic you are. That means how active the language area in the brain is when it comes to pairing letters with sounds.

That means that some dyslexic people can, to a certain degree, learn some letter sounds while others cannot. Therefore, there is no particular way that we dyslexic people read. But what we all have in common is that we can practice in a way in which each of us compensates for the less-active language areas in the assembly line to the best of our ability.

One way that a dyslexic brain can learn to read is by remembering words.

This is done by taking a “picture” of the word and storing it.

As a dyslexic, you can “remember-read” long words if you have seen them often enough.

You should not be surprised if your football-enthusiastic child can read “football station” but not the word “read.” It might be because your child wants to read about football and, therefore, listens to and sees the words connected to the sport many times.

Another example is the word “whiskey.” It has a particular pattern. The H goes across the line at the beginning of the word, the K crosses the line in the middle of the word, and the Y goes under the line at the end.

When I see this shape, my brain tells me that it says “whiskey.” I would not be able to read it by using the sounds of the letters. My brain uses a recognition pattern. That means my brain is compensating by using my memory to recognize the visual impression I am getting from the form that the word “whiskey” is creating.

When the brain has seen a particular word enough times, combined with the brain being told how it sounds, then the brain can remember it.

The challenging part is that it demands a lot of energy for the brain to remember all words. This is not the way it is for the average reader, who only has to learn the letter sounds and can then read through the words.

Accepting the dyslexia

Is your child also finding it difficult to talk about their thoughts and emotions when the letters are teasing them?

Motivation to read

Would you also like to motivate your child to read more? And is it difficult to find the right “carrot”?

Learning styles as a dyslexic person

Many believe that a dyslexic person has more difficulties learning and fewer options for further education. But that is not true…

THE WORKING MEMORY FOR DYSLEXIC PEOPLE IS WORKING OVERTIME

When it comes to memory, it is often said that a dyslexic person has a decreased working memory.

That is both correct and wrong at the same time.

Let me start by explaining how our memory works.

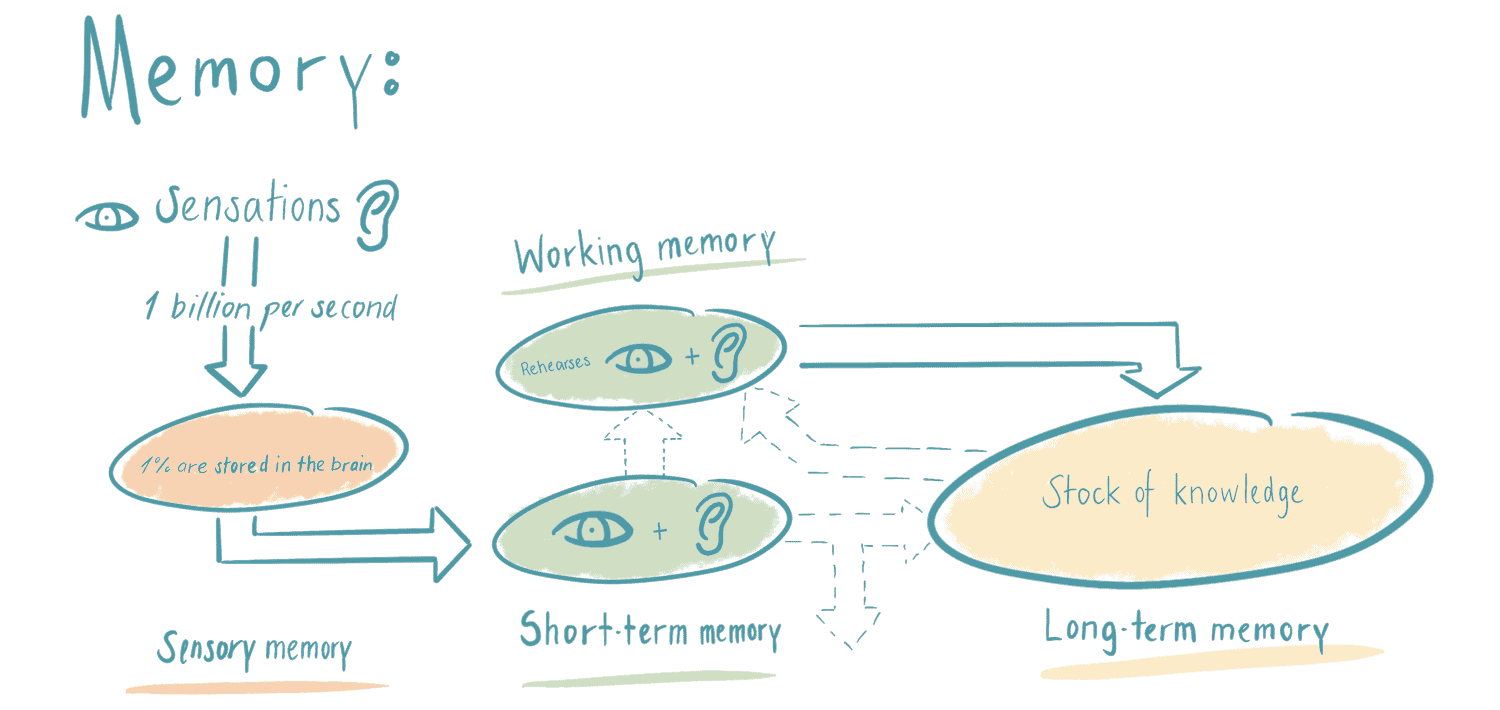

First, our brain receives a lot of sensory perceptions—no less than 1 billion per second.

The brain absorbs one percent of the sensory perceptions.

The sensory perceptions are processed in the short-term memory, either as a sound that is converted to words in our inner ear or as visual perceptions for our inner camera.

If we do not use what enters our short-term memory, then it will either be stored without further ado or disappear.

However, if we use the impressions we get into the brain, we activate the working memory. That means that the working memory stores and processes the perceptions while we use the capacity of focus that we have at our disposal.

Short-term memory and working memory are, therefore, not quite the same.

The things we process in the working memory will be stored in long-term memory. At the same time, we utilize old knowledge from the long-term memory and combine it with the new impressions in the working memory.

Let me give you a simple example.

Let’s say we are reading a new word: “houseboat.” The visual impression of the picture we see on paper gets into the short-term memory, and the working memory is immediately put to work.

We have previously learned what the words “house” and “boat” sound like. We pick that up from the long-term memory and use the knowledge to read the word “houseboat.”

For a dyslexic person, there is nothing different about the various memory functions (including the working memory) compared to people that do not have dyslexia.

However, the working memory is under pressure in people with dyslexia because we cannot recall any knowledge about the sounds of the letters in the long-term memory. We have to go and find each word, as well as remember both how they look and how they are pronounced.

And if we haven’t seen the word before, there is no help from our long-term memory.

It does not allow for a lot of space in the working memory to understand the meaning of the text and pair it with other types of knowledge we have stored in the long-term memory.

Some research shows that people with dyslexia are often challenged with their working memory when it is about reading and spelling.

Other research shows that dyslexic people do not have problems with the working memory when it is about visual information, such as pictures.

Remember that this article is based on scientific papers, but the dyslexic brain is still being researched, so new knowledge may arise in the future.

Nevertheless, a basic understanding of how the brain and memory function is a foundation for your child to realize that nothing is wrong. Your child’s brain is just functioning differently than those of other children that do not have dyslexia, and it is possible to compensate for this through different areas in the brain.

Furthermore, IT tools such as recital can relieve the brain when it is reading, so it does not have to use all its energy on remembering both the word and its sound. Instead, your child can focus on understanding the meaning of the text.

The joy of learning new things

Feelings are the primary motor for learning. Do you also wish that your child would be more eager to learn new things in school?

Difficulty with learning how to read

Does my child have reading difficulties or dyslexia? You can see that your child is struggling with the letters, but how does your child progress?

Jesper Sehested

Dyslexic, author, speaker and mentor

Sources:

Elbro, Carsten (2007), ‘Læsevanskeligheder’

Lauridsen, Ole (2016), ‘Hjernen og Læring’

Samuelsson, Stefan, m.fl., (2012), ‘Dysleksi og andre vanskeligheder med skriftsproget’

Willis, Judy (2015), ‘Teaching The Brain to Read’